A night out in Berghain, one of the greatest techno clubs in Berlin and the hardest to get in, leaves plenty of things to think and feel over. Techno sounds, spacious factory building size of an ancient temple (electrical plant in fact), church coloured light through thin windows and half-naked gay guys wearing leather pants and leather belts crossed on their muscular chests, intense sex vibes in the air and the amazing perception difference involving mdma.

I found a nice text which sort of explains it all a bit. It was written by Louis-Manuel Garcia (from an essay "Vagueness and Liquidarity: Solidarity, Belonging, and Ethics on the Dancefloor in Paris and Berlin”, the guy actually is a PhD candidate in Chicago and I envy him about the research object a lot) posted in Slow Travel Berlin.

Berghain: a nightclub that has become an institution of the Berlin techno scene, also taking on mythical proportions in the global techno and house scenes.

The club is in fact a reincarnation of an earlier Berlin nightclub, Ostgut (1998-2003), which was located in the empty Ostgüterbahnhof railway shipping warehouse near the Ostbahnhof S-Bahn/railway station in the Friedrichshain district (in former East Berlin).

Ostgut closed in 2003, the building was subsequently demolished, and the vacant space became part of the property for the multi-use sports and entertainment arena, O2 World, the naming rights of which were bought by mobile telecommunications company Telefónica O2 Germany in 2006.

With some financial support from municipal government and outside investors, Ostgut reopened as Berghain in 2004 in a DDR-era electrical plant on the other side of Ostbahnhof’s railway tracks.[1] The new name, “Berghain,” is a portmanteau taken from the final syllables of the names of the two districts that flank the location: Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain (former West and East Berlin, respectively).

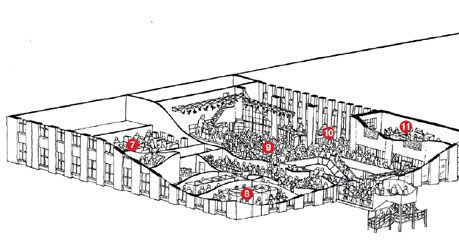

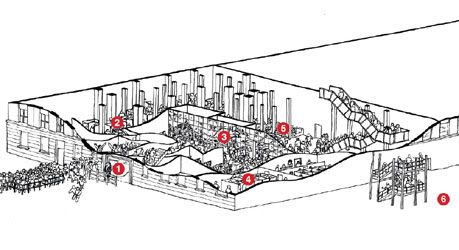

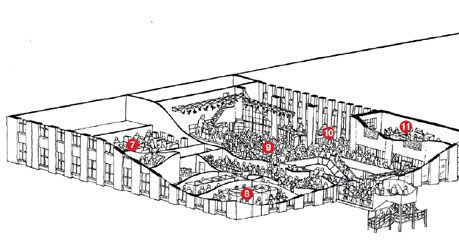

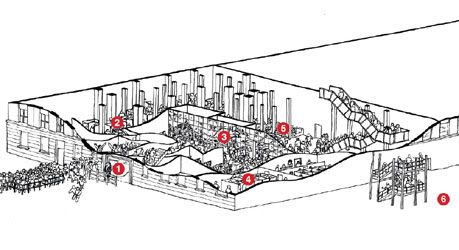

The building in which Berghain is located was built between 1953 and 1954 in the socialist neoclassical style, with alternating pilasters and lattice windows running the height of the building, underlined by a band of rusticated masonry around the base.[2] Although there are essentially three levels to the building, each level has a height of approximately 9 meters (30 feet).[3]

The ground floor includes a relatively small ticket booth area, followed by a large entry hall with a coat-check and an art installation by Polish artist, Piotr Nathan, entitled Rituale des Verschwindens [Rituals of Disappearance] (2004) and composed of 175 1m2 aluminum tiles.[4] The remainder of the floor is dedicated to a bar area and a large darkroom space, reserved for (mostly) male-male sexual play.

Suspended steel stairs lead up to Berghain, the former turbine room, with 18m-high ceilings (60 ft.), a dancefloor that can easily hold 500 people, and seven massive FunktionOne speaker stacks.[5] The second floor also holds two bars, another darkroom, a mezzanine with an ice cream bar, and large unisex bathrooms.

Another set of steel stairs on one side of the main dancefloor leads to Panorama Bar, a second dancefloor located in the former control room of the electrical plant. This space includes a wrap-around bar covered in black rubber, and large-format prints of Wolfgang Tillmans photographs, including two from his abstract “Freischwimmer” series, and one of a woman sitting on a chair, naked below the waist, with her spread legs exposing her shaved vagina with pink, swollen labia.[6]

The DJ spins at a table suspended bychains from the ceiling, separated from the crowd by a railing of steel tubing decorated with worn-out dials and needle-meters (left over from the room’s previous life), which also serves as a shelf for drinks. The floor-length windows running one side of the room are covered by mechanized metal blinds, which the lighting technician opens during moments of musical climax to allow the morning sun to wash over the crowd.

The rest of this upper floor includes another set of unisex bathrooms, another bar, several alcoves (old storage lockers that have been modified and cushioned), and a smoking area. A door on the eastern side of the ground floor opens out onto a patio space—including another bar, a dancefloor covered by netting, and plenty of cushions and alcoves—which opens up from midday till at least dusk of the following day, weather permitting. Throughout the club, couches have been fashioned out of 1,462-kilogram (3,223-pound) concrete channel sections.

All of this space, which has a capacity of 1,500 people, occupies only half of the building. The upper two levels of the rear half of the building are as of yet undeveloped, although the management has proposed turning the space into a multi-use performance and exhibition space (the project is dubbed “Kubus” by the architectural firm, Karhard Architektur).

In late 2009, Berghain was awarded 1.5 Million Euros in government funds to finance this project and other renovations, which comes from the coffers of the Vermögen der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR—that is, of the fund held collectively by the socialist political parties and citizens’ associations of the former German Democratic Republic.[7]

The remainder of the ground floor level is known as the Lab.Oratory, a (gay male) sex club that is considered one of the most “hardcore” gay fetish clubs in Berlin. This male-only space usually remains separate from the mixed-gender (but predominantly queer) space of Berghain/Panorama Bar: it maintains a separate, less visible entrance at the side of the building and it advertises its events on a separate website. Nonetheless, the doors between the two sections of the building are opened once a year at New Year’s Eve.

Although Berghain/Panorama Bar and Lab.Oratory operate mostly as separate establishments, this does not mean that sexual play is limited to the sex club: there are two very active darkrooms in Berghain and, since Lab.Oratory opens and closes earlier, its patrons will often come up to Berghain afterwards.

Ostgut, Berghain’s precursor, actually began as an itinerant gay fetish night called “Snax,” which eventually found a permanent home at Ostgut in 1998; up to the time of this writing, Berghain holds a special “Snax” fetish night every year on the weekend of Holy Week, in Easter.

On a regular night at Berghain, the sexual escapades of the darkrooms often spill over to the bathroom stalls, the half-lit alcoves lining the hallways, and sometimes right to the middle of the dancefloor or at the bar. In fact, it has become something of a cliché in first-hand accounts of Berghain to claim that one had been witness to some form of penetrative sex act in a well-lit area of the club; this cliché is not complete, however, without also claiming that none of the surrounding partygoers were in the slightest bit fazed by such antics.

This is not to say that such clichés are false; quite the contrary, the crowds at Berghain and Panorama Bar provide a constant supply of salacious anecdotes that sustain its reputation as a place of unlimited hedonism and permissiveness. This permissiveness also extends to the consumption of illicit substances, which are an undeniable part of marathon partying that takes place at Berghain.

It is both to protect these practices and to preserve this reputation that the club staff are not at all permissive about one thing: photography. Any form of photography is strictly forbidden within the walls of the club. The front door, when open, displays a sign that shouts, “Taking photos is not allowed!” in English, French, Russian, and German; this sign has become such a symbol of Berghain’s amalgam of excessiveness and protectiveness, it has been chosen to grace the final page of the English translation of Tobias Rapp’s Lost and Sound: Berlin, Techno und der Easyjetset.[9][10]

While being searched in front of the box office, any camera you have will be torn from your hands and checked at behind the box office desk; they don’t even trust you to walk to the coat check and leave it there. If your mobile phone has a built-in camera, the security personnel will wave your phone in front of your face and recite the standard warning, in German or English, “No pictures inside, OK? If we see you taking a picture, we throw you out and it’s Hausverbot [permanent banishment from the premises] for you. Got it?”

This is no mere formality; every time I have witnessed this speech, the vocal intonation has been emphatic, the gaze sincere, and their gestures sharp. Nor is this an idle threat; on several occasions I have seen someone attempt to snap a picture of the DJ or the crowd with her or his camera-phone, only to have bouncer materialize next to her or him, snatch the camera, and frog-march the bewildered clubber to the exit.

When asked, the staff will always justify this policy as being essential to creating a safe space of erotic and pharmacological experimentation; this is undoubtedly true, but it also contributes to a separation of inside and outside experience: what happens in Berghain only circulates outside as gossip, tall tales, fragmented memories, and nostalgia.

Similarly, many descriptions of Berghain note that there are no mirrors or reflective surfaces anywhere in the club, suggesting that this was done deliberately to prevent partygoers from feeling embarrassed about their messy state and going home. While all of these practices and discourses constantly reproduce Berghain’s reputation as a site of excess, experimentation, unraveling, and freedom, this club also has a reputation as a global epicenter for techno and house music.

Philip Sherburne, a prominent reviewer for the online music publication Pitchfork, suggested that Berghain “is quite possibly the current world capital of techno, much as E-Werk or Tresor were in their respective heydays.”[11] The readers of Resident Advisor, a long-standing online EDM community, voted Berghain/Panorama Bar the best club in the world in 2008, while readers of DJ Mag voted it best club in the world in 2009.

Most profiles of the club echo Sherburne, praising the booking policy (a balance of high-profile DJs, legendary veterans, and rising talent), the appreciative and engaged crowd, the powerful but clean sound system, the marathon DJ sets (which gives DJs more freedom to range widely in style and mood), and the relatively low cost (compared to clubs of similar caliber in other European capitals). Several of my contacts in both Berlin and Paris claimed that the roster of DJs for an average night at Berghain would be worthy of a massive, “highlight of the season” event in any other city.

Along with Berghain’s reputation for being a space of freedom, hedonism, musical connoisseurship, and intense experience comes a reputation for being severely, inscrutably, and at times arbitrarily selective at the door. Berghain’s bouncers are notorious for enforcing a stringent but elusive door policy, the precise parameters of which are never divulged by the staff and can be inferred only from observing the fate of those ahead of you in line.

There exists a constantly churning discourse within EDM networks about how to avoid being turned away at the door: don’t look too glamorous; look queer; don’t act like a tourist; don’t look too young; don’t show up as a group of straight men or women; dress eccentrically; go alone; if you don’t speak German, don’t speak your native tongue in line and learn how to say “Hello” and “One, please,” in German; and so on. At least one of these unspoken rules is widely known and broadcast among Berlin clubbers: no large groups.

Luis-Manuel Garcia is a PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at the University of Chicago. His doctoral project focuses on intimacy and affect in crowds, as they manifest on the dancefloors of Electronic Dance Music events (i.e., “house” music, “techno,” etc.). This is a multi-sited ethnographic project that follows a translocal “scene,” a circuit of moving bodies and music between Chicago, Paris, and Berlin.

The above text is from an essay entitled, “Vagueness and Liquidarity: Solidarity, Belonging, and Ethics on the Dancefloor in Paris and Berlin,” which will appear in the forthcoming collection Music and Sociality in Urban Europe, edited by Fabian Holt and Carsten Wergin. It originally appeared on Luis-Manuel’s blog, where you can also find an equally thorough article on the MediaSpree debate.

I found a nice text which sort of explains it all a bit. It was written by Louis-Manuel Garcia (from an essay "Vagueness and Liquidarity: Solidarity, Belonging, and Ethics on the Dancefloor in Paris and Berlin”, the guy actually is a PhD candidate in Chicago and I envy him about the research object a lot) posted in Slow Travel Berlin.

Berghain: a nightclub that has become an institution of the Berlin techno scene, also taking on mythical proportions in the global techno and house scenes.

The club is in fact a reincarnation of an earlier Berlin nightclub, Ostgut (1998-2003), which was located in the empty Ostgüterbahnhof railway shipping warehouse near the Ostbahnhof S-Bahn/railway station in the Friedrichshain district (in former East Berlin).

Ostgut closed in 2003, the building was subsequently demolished, and the vacant space became part of the property for the multi-use sports and entertainment arena, O2 World, the naming rights of which were bought by mobile telecommunications company Telefónica O2 Germany in 2006.

With some financial support from municipal government and outside investors, Ostgut reopened as Berghain in 2004 in a DDR-era electrical plant on the other side of Ostbahnhof’s railway tracks.[1] The new name, “Berghain,” is a portmanteau taken from the final syllables of the names of the two districts that flank the location: Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain (former West and East Berlin, respectively).

The building in which Berghain is located was built between 1953 and 1954 in the socialist neoclassical style, with alternating pilasters and lattice windows running the height of the building, underlined by a band of rusticated masonry around the base.[2] Although there are essentially three levels to the building, each level has a height of approximately 9 meters (30 feet).[3]

The ground floor includes a relatively small ticket booth area, followed by a large entry hall with a coat-check and an art installation by Polish artist, Piotr Nathan, entitled Rituale des Verschwindens [Rituals of Disappearance] (2004) and composed of 175 1m2 aluminum tiles.[4] The remainder of the floor is dedicated to a bar area and a large darkroom space, reserved for (mostly) male-male sexual play.

Suspended steel stairs lead up to Berghain, the former turbine room, with 18m-high ceilings (60 ft.), a dancefloor that can easily hold 500 people, and seven massive FunktionOne speaker stacks.[5] The second floor also holds two bars, another darkroom, a mezzanine with an ice cream bar, and large unisex bathrooms.

Another set of steel stairs on one side of the main dancefloor leads to Panorama Bar, a second dancefloor located in the former control room of the electrical plant. This space includes a wrap-around bar covered in black rubber, and large-format prints of Wolfgang Tillmans photographs, including two from his abstract “Freischwimmer” series, and one of a woman sitting on a chair, naked below the waist, with her spread legs exposing her shaved vagina with pink, swollen labia.[6]

The DJ spins at a table suspended bychains from the ceiling, separated from the crowd by a railing of steel tubing decorated with worn-out dials and needle-meters (left over from the room’s previous life), which also serves as a shelf for drinks. The floor-length windows running one side of the room are covered by mechanized metal blinds, which the lighting technician opens during moments of musical climax to allow the morning sun to wash over the crowd.

The rest of this upper floor includes another set of unisex bathrooms, another bar, several alcoves (old storage lockers that have been modified and cushioned), and a smoking area. A door on the eastern side of the ground floor opens out onto a patio space—including another bar, a dancefloor covered by netting, and plenty of cushions and alcoves—which opens up from midday till at least dusk of the following day, weather permitting. Throughout the club, couches have been fashioned out of 1,462-kilogram (3,223-pound) concrete channel sections.

All of this space, which has a capacity of 1,500 people, occupies only half of the building. The upper two levels of the rear half of the building are as of yet undeveloped, although the management has proposed turning the space into a multi-use performance and exhibition space (the project is dubbed “Kubus” by the architectural firm, Karhard Architektur).

In late 2009, Berghain was awarded 1.5 Million Euros in government funds to finance this project and other renovations, which comes from the coffers of the Vermögen der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR—that is, of the fund held collectively by the socialist political parties and citizens’ associations of the former German Democratic Republic.[7]

The remainder of the ground floor level is known as the Lab.Oratory, a (gay male) sex club that is considered one of the most “hardcore” gay fetish clubs in Berlin. This male-only space usually remains separate from the mixed-gender (but predominantly queer) space of Berghain/Panorama Bar: it maintains a separate, less visible entrance at the side of the building and it advertises its events on a separate website. Nonetheless, the doors between the two sections of the building are opened once a year at New Year’s Eve.

Although Berghain/Panorama Bar and Lab.Oratory operate mostly as separate establishments, this does not mean that sexual play is limited to the sex club: there are two very active darkrooms in Berghain and, since Lab.Oratory opens and closes earlier, its patrons will often come up to Berghain afterwards.

Ostgut, Berghain’s precursor, actually began as an itinerant gay fetish night called “Snax,” which eventually found a permanent home at Ostgut in 1998; up to the time of this writing, Berghain holds a special “Snax” fetish night every year on the weekend of Holy Week, in Easter.

On a regular night at Berghain, the sexual escapades of the darkrooms often spill over to the bathroom stalls, the half-lit alcoves lining the hallways, and sometimes right to the middle of the dancefloor or at the bar. In fact, it has become something of a cliché in first-hand accounts of Berghain to claim that one had been witness to some form of penetrative sex act in a well-lit area of the club; this cliché is not complete, however, without also claiming that none of the surrounding partygoers were in the slightest bit fazed by such antics.

This is not to say that such clichés are false; quite the contrary, the crowds at Berghain and Panorama Bar provide a constant supply of salacious anecdotes that sustain its reputation as a place of unlimited hedonism and permissiveness. This permissiveness also extends to the consumption of illicit substances, which are an undeniable part of marathon partying that takes place at Berghain.

It is both to protect these practices and to preserve this reputation that the club staff are not at all permissive about one thing: photography. Any form of photography is strictly forbidden within the walls of the club. The front door, when open, displays a sign that shouts, “Taking photos is not allowed!” in English, French, Russian, and German; this sign has become such a symbol of Berghain’s amalgam of excessiveness and protectiveness, it has been chosen to grace the final page of the English translation of Tobias Rapp’s Lost and Sound: Berlin, Techno und der Easyjetset.[9][10]

While being searched in front of the box office, any camera you have will be torn from your hands and checked at behind the box office desk; they don’t even trust you to walk to the coat check and leave it there. If your mobile phone has a built-in camera, the security personnel will wave your phone in front of your face and recite the standard warning, in German or English, “No pictures inside, OK? If we see you taking a picture, we throw you out and it’s Hausverbot [permanent banishment from the premises] for you. Got it?”

This is no mere formality; every time I have witnessed this speech, the vocal intonation has been emphatic, the gaze sincere, and their gestures sharp. Nor is this an idle threat; on several occasions I have seen someone attempt to snap a picture of the DJ or the crowd with her or his camera-phone, only to have bouncer materialize next to her or him, snatch the camera, and frog-march the bewildered clubber to the exit.

When asked, the staff will always justify this policy as being essential to creating a safe space of erotic and pharmacological experimentation; this is undoubtedly true, but it also contributes to a separation of inside and outside experience: what happens in Berghain only circulates outside as gossip, tall tales, fragmented memories, and nostalgia.

Similarly, many descriptions of Berghain note that there are no mirrors or reflective surfaces anywhere in the club, suggesting that this was done deliberately to prevent partygoers from feeling embarrassed about their messy state and going home. While all of these practices and discourses constantly reproduce Berghain’s reputation as a site of excess, experimentation, unraveling, and freedom, this club also has a reputation as a global epicenter for techno and house music.

Philip Sherburne, a prominent reviewer for the online music publication Pitchfork, suggested that Berghain “is quite possibly the current world capital of techno, much as E-Werk or Tresor were in their respective heydays.”[11] The readers of Resident Advisor, a long-standing online EDM community, voted Berghain/Panorama Bar the best club in the world in 2008, while readers of DJ Mag voted it best club in the world in 2009.

Most profiles of the club echo Sherburne, praising the booking policy (a balance of high-profile DJs, legendary veterans, and rising talent), the appreciative and engaged crowd, the powerful but clean sound system, the marathon DJ sets (which gives DJs more freedom to range widely in style and mood), and the relatively low cost (compared to clubs of similar caliber in other European capitals). Several of my contacts in both Berlin and Paris claimed that the roster of DJs for an average night at Berghain would be worthy of a massive, “highlight of the season” event in any other city.

Along with Berghain’s reputation for being a space of freedom, hedonism, musical connoisseurship, and intense experience comes a reputation for being severely, inscrutably, and at times arbitrarily selective at the door. Berghain’s bouncers are notorious for enforcing a stringent but elusive door policy, the precise parameters of which are never divulged by the staff and can be inferred only from observing the fate of those ahead of you in line.

There exists a constantly churning discourse within EDM networks about how to avoid being turned away at the door: don’t look too glamorous; look queer; don’t act like a tourist; don’t look too young; don’t show up as a group of straight men or women; dress eccentrically; go alone; if you don’t speak German, don’t speak your native tongue in line and learn how to say “Hello” and “One, please,” in German; and so on. At least one of these unspoken rules is widely known and broadcast among Berlin clubbers: no large groups.

Luis-Manuel Garcia is a PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at the University of Chicago. His doctoral project focuses on intimacy and affect in crowds, as they manifest on the dancefloors of Electronic Dance Music events (i.e., “house” music, “techno,” etc.). This is a multi-sited ethnographic project that follows a translocal “scene,” a circuit of moving bodies and music between Chicago, Paris, and Berlin.

The above text is from an essay entitled, “Vagueness and Liquidarity: Solidarity, Belonging, and Ethics on the Dancefloor in Paris and Berlin,” which will appear in the forthcoming collection Music and Sociality in Urban Europe, edited by Fabian Holt and Carsten Wergin. It originally appeared on Luis-Manuel’s blog, where you can also find an equally thorough article on the MediaSpree debate.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий